When it comes to climbing mountains, there is no gain without a little pain.

As the first rays of sunlight peaked over the blanket of clouds above which we stood, the sky gradually shifted from a surreal blend of pink and purple to a cornflower-blue canvas streaked with shafts of golden light.

We were on top of Southeast Asia’s highest mountain, Mount Kinabalu, on the spiky summit of Low’s Peak at 4,095.2 metres. It was this moment that made two days’ worth of climbing, a 2am start and a knee-crunching decent completely worthwhile.

Despite the challenges, witnessing this sublime sunrise is not as difficult as you might think. Anyone with a decent level of fitness can summit Mount Kinabalu.

At the foot of the mountain

Mount Kinabalu is a couple of hours away from the city of Kota Kinabalu on the northern coast of Malaysian Borneo. We arrived at Kinabalu Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2000, late in the afternoon. I was armed with just a daypack, having sent the rest of my luggage on to the Shangri-La Rasa Ria, where I was already looking forward to a full body massage.

Through a gap in the clouds, I glimpsed the top of the mountain I was here to summit. Rising grandly above the lush rainforest valleys and emerald-carpeted hills of the park, the jagged granite peaks of Mount Kinabalu looked unnervingly far away.

We woke early the next morning for a big breakfast before driving to the gate to begin our climb. Within our group were a mixture of fitness levels, some of us feeling fully prepared for the challenge, whilst others felt physically ill at the prospect of what lay ahead. We snapped a group photo, showed our permits at the first of three checkpoints, and started the hike.

Stairway to heaven

The first part of the climb was a seemingly endless series of slightly-too-high steps reinforced with wooden beams. There were no stretches of flat ground and the ascent was relentless.

Surrounded by dense vegetation, the path was sheltered from the sun, but within a mere half hour the humidity had me dripping with sweat. The air became thinner as we climbed and for the first couple of hours I experienced a weird sensation of being continuously out of breath, but with no tiredness or pain in my legs.

We hiked ever upwards through the fertile, misty cloud forest. Gnarled vines wrapped their arms around ancient tree trunks. Mountain squirrels that looked like squirrel-chipmunk hybrids (I grew to call them ‘chirrels’) sprinted from tree to tree on the lookout for stray scraps of food at the rest stations we passed.

As I climbed, I made sure that I continued to sip from my water bottle. I’d bought about two litres for the first leg of the climb, which – for my speed – was just about right. If I’d been hiking for any longer, I would have wanted more.

TOP TIP: Bring a camelback to keep your hands free whilst being able to sip water throughout the hike. Sipping water little and often helps combat altitude sickness.

We’d been warned to take the first couple of kilometres slowly, but it’s equally important to avoid climbing at a slower than comfortable pace, so I kept up a brisk cadence.

As we climbed higher and higher, reaching the subalpine area, the flora became sparser and drier, the foliage changing from rich vegetation to tough shrubs and small, hardy-looking trees with greying bark. Leaving the mist and cover of the cloud forest behind us, I could now see the mountain’s bare, grey, granite peaks jutting up in front of me.

The stairs finally ended and in their place were uneven boulders. I tried to pick out a path that involved the smallest steps. By now we were passing many climbers on their way down, all of whom – somewhat ominously – wished us, ‘Good luck!’

Finally, I saw a small building perched on the side of the mountain: Laban Rata guesthouse, our stop for the night. After three and a half hours of climbing, I sat down on a rock at the top of the trail, munched my banana (also good for staving off altitude sickness) and waited for the others to arrive.

TOP TIP: Buy some rehydration sachets with electrolytes at Laban Rata, add it to a large 2L bottle of water and drink it all. This should help with any effects of the altitude.

Waking in the dark

Although we’d all heard horror stories about how bone-chillingly cold it was up at Laban Rata, our tiny room – with the combined body heat of six people – was like a furnace and most of us spent the night feverishly stripping off the excessive layers in which we’d gone to sleep.

Our alarms went off at 1.30am. After ‘supper’, which was actually the first breakfast of the day, we strapped on our head torches and stepped out into the night.

Summiting with the sun

The most important aim of the summit climb for me was to pace myself: we had a long time to reach Low’s Peak and arriving early would only result in us having to sit in the freezing darkness waiting for the sun to show.

I asked our guide to act as our pacer. Having climbed the mountain over 300 times, he knew what he was doing.

TOP TIP: You’ll need a variety of layers for the summit climb, but don’t wear them all at once, as you’ll be warm when climbing. The temperature at the summit, however, can be below freezing.

After yet more steps, we made our way onto the sheer granite rock face that characterises the highest part of Mount Kinabalu and where the way was marked with a white rope. Balancing on narrow ridges along the side of the mountain, we edged our way in a zig-zag up and up, gripping the rope for balance.

The pools of light from our head torches were the only source of illumination and we had no way of gaging the drop to our side. For me, this was excellent: what I couldn’t see couldn’t scare me. For others, it was their undoing and one of our team turned back.

A glance up to the side revealed the pinpricks of yellow light from the villages and towns at the foot of the mountain. Looking up, we were treated to a sky full of glittering stars.

We passed the final checkpoint – only those who reach this mark before 5am can continue – and began the slow, steady trudge on tiptoe up the steep slope, following the white rope that lead up and up.

A shooting star zipped across the dark, sparkling sky. Far below us was a winding trail of tiny, flickering lights belonging to fellow climbers as they snaked their way up the mountain.

After one last scramble up a wall of rocks, suddenly we arrived at Low’s Peak: 4,095.2 metres.

Despite our pacing we still arrived an hour before the 6.15am sunrise. However, looking out from the peak, I saw that the horizon was already illuminated by a red glow.

As dawn gradually crept in, night’s dark cloak was dragged back to reveal the landscape beneath us. Craggy peaks rose out of a frothy sea of clouds. A golden haze marked the horizon, growing stronger and stronger until the first rays of sunlight finally broke free. The sky changed from dreamy lavender to gilded blue and the top of the clouds were bathed in sunshine.

Morning had broken and it was time to start our descent.

The long way down

The journey down was, for me at least, much harder than the ascent. After stopping briefly for breakfast number two at Laban Rata, we wasted no time in continuing down the mountain.

With the constant, steep descent came the return of my runner’s knee. However, slowing down would not have resulted in less pain, so we continued to scurry down as quickly as possible.

Having decided ‘good luck’ sounded too sinister, I greeted puffed-out climbers heading up the mountain with a (hopefully) reassuring, ‘It’s worth it!’

With a couple of kilometres to go, I glanced up at a girl walking in the opposite direction and was about to smile politely and deliver my motivational message, when I recognised her as a good friend of mine from London who was currently travelling in Asia. As luck would have it, she happened to be on the same mountain on the exact same day as me. After spending 15 minutes catching up and crossing our fingers the forecasted rains wouldn’t come to anything, we were off again.

By the time I reached the bottom, my legs were like jelly and I could barely manage the cruelly positioned flight of stairs up to the final checkpoint at the entrance gate.

A happy ending

While we waited for the others to arrive, a cold Tiger beer went down extremely well. It had started to rain; we’d just missed it. In fact, we’d been very lucky with the weather, especially as Mount Kinabalu receives an average of 2,700 millimetres of rain a year (over four times more than London).

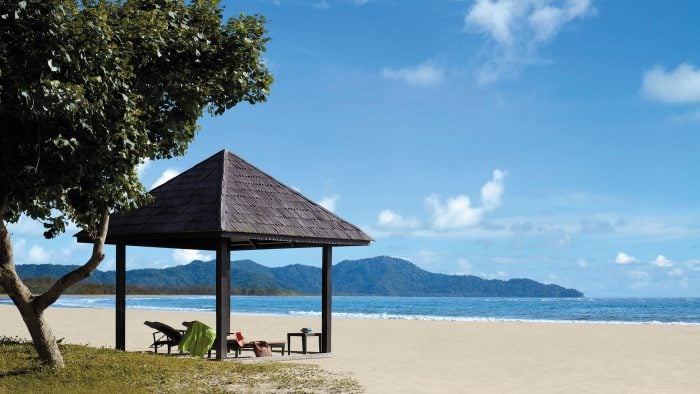

By 5.30pm, everyone had reached the bottom of the mountain and we headed off to the Shangri-La Rasa Ria, the thought of which had kept many of us motivated over the past couple of days.

After a much-needed shower and dinner at the Shangri-La’s Indian restaurant Naan we split into the groups that had become familiar throughout the trip: half took their weary legs off to bed, while the rest of us decided to celebrate with several bottles of wine at the beach bar.

We spent the following day indulging in a massage that was half bliss (upper body) and half torture (my still very tender legs) and watching the young orangutans swinging around at the Shangri-La’s onsite sanctuary.

Back in London after three flights, I could barely walk from the pounding my legs had received on the way down Mount Kinabalu, but, for those moments sat above the cloud line on Southeast Asia’s highest peak, it really was worth it.

I travelled with Royal Brunei Airlines, who fly to Kota Kinabalu from London.