The explorer, author and filmmaker talks to Jacada about his greatest challenges, inspiration and his hopes to seek out a lost tribe of New Guinea.

The explorer and adventurer Benedict Allen has an astounding repertoire of extraordinary stories, having ventured across the Amazon Basin at its widest point, crossed the Gobi desert alone, and covered the entire length of the Namib desert, while connecting with the local people and documenting his experiences by handheld camera. The resulting TV series, for the BBC and National Geographic among others, have captivated viewers with rare insights into these fascinating cultures, making him best known for his contact with some of the world’s remote indigenous tribes. “The people, for me, are a window into the landscape,” he says, “I’m interested in places, but for me the way into those places is through the locals.” As an author, Benedict has written 10 books, including the bestsellers The Skeleton Coast and Edge of Blue Heaven, with his latest novel due out next year.

You’ve said that you were influenced by your father who was a test pilot, but have you been influenced by any other explorers or adventurers?

Yes. As a boy, I wanted to be an explorer and some kind of adventurer because of my dad, but it was when I saw him flying bombers and exciting images like that, that I started reading about explorers. Captain Cook was a big influence on me. He’s an iconic figure, but he was also a navigational genius, with amazing attention to detail and the ability to get himself in the right place at the right time.

It was also Captain Cook’s attitude to the indigenous people that hugely impressed me. He was able to see them simply as local people, instead of savages or from the Stone Age. There’s an extraordinary story in which Cook got into a rowing boat, from his ship, to approach a Maori who was doing a fearsome display, waggling his tongue and shouting. Cook just got out of his boat, showed he wasn’t armed and hugged the man that was raising his spear.

What is it that draws you to a particular part of the world? How do you choose your next destination?

I go to the local people, like Captain Cook did, but in my own way, to settle down with them for a while. In the Amazon, I lived with them and learnt their skills, and that’s how I learnt to survive. This has become more and more important to me.

I found in the Amazon that the indigenous people there see the forest as their food, shelter and medicine. It’s all about finding people who I think morally I can visit, finding people who have the skills, then setting out alone to see if I have learnt those skills by pushing myself to the limit.

So are you more interested in the people of a place than other factors such as the landscape?

Yes, but the people, for me, are a window into the landscape. I’m interested in places, but for me the way into those places is through the locals.

Which expedition are you most proud of?

Well, I’ve done a few firsts; I was the first person allowed to walk up the Namib desert, and I crossed the Gobi by myself. The one that was technically the most difficult was crossing the whole of the Amazon Basin at its widest point. That took seven and a half months. For me, this was to see if I’d learnt enough to really see it as somewhere I could exist in, but the journey was very dangerous. It was a huge challenge and I pulled it off because of the local Matses people who took me in and gave me a chance.

What was your most challenging moment?

On my very first expedition I got two sorts of malaria and essentially almost starved to death, so I had to make the decision to eat my dog. That was obviously a huge challenge and very sad at the time, but it meant I could live.

Then when I was crossing the Amazon Basin, I found myself being shot at and chased by hitmen. They belonged to Pablo Escobar and I’d been seen by his camp where they were hiding out. I was in a canoe and they were in their boats, so I just had to keep ducking, until I could run into the forest.

That was a great lesson as once I sat down on the forest floor, I realised I was safe. The forest is so thick that the people on the river just couldn’t see me. It was evidence that the forest could be on your side, if you only worked with it rather than against it.

Where have you felt the closest connection with the community?

I went through an initiation ceremony with the Niowra in Papua New Guinea to make me a man that’s as strong as a crocodile. After the disaster on my first expedition, I decided I needed to train myself up by going through this ceremony. It was a huge privilege, as it’s a secret ceremony that no outsiders had been through before, but it was also hugely tough.

We had six weeks locked away with the other initiates and we were cut with bamboo to give us crocodile marks, which I still have to this day. It was an extraordinary experience, all about how you have to work together.

The lesson, which I suppose I haven’t really learnt, is that the forest is too big to take on, which is why they gather in tribal communities; tight communities that ensure people work together. They wanted me to settle down with them and marry, and I have been back since, but I found it very difficult to accept their culture. It was very macho, male driven and brutal; they encourage anger, hence the crocodile cult. The crocodile is very aggressive and territorial, and they look to these values.

The Matses people in the Amazon are much more sympathetic. They emanate the jaguar – I suppose for its stealth, intelligence and agility – but they are also quiet people. I found it easier to get to know them, but it’s important to say that these are my values as an outsider.

Is there an individual you’ve met on your travels that has had an impact on you?

There was a man called Pablito who was one of the Matses. He was the one who said I could settle down with them and that they’d teach me how to live in the forest. I had the most difficult bit of forest ahead of me, so I had to find a way of pulling the journey off on my own.

Pablito accepted me into his family and helped me read the forest by picking out individual species that could be on my side. I was aware that my life was in his hands. You’re assailed by all these species that have evolved over hundreds of years, and all these species are battling away, trying to block each other’s light and knock each other out. From this wall of noise, he enabled me to pick up certain sounds and shapes, like the types of palms you can make into a shelter, and leaves, berries and animals you can eat.

What’s your most memorable experience with the local food?

What springs to mind is the sago grub I had to eat in New Guinea, very early in my travelling life. I was handed a whole handful of these wriggly sago grubs. The people I was with just popped them into their mouths. I put mine in my mouth and this sago grub decided it wasn’t going to die. It stopped itself at the bottom of my throat, slowly turned around, walked up my throat and jumped out.

I did eat these again but not for quite a few years. From then on I insisted on them being fried up. They’re ok actually, with a buttery taste; they’re quite nice.

Where have you been most blown away by the scenery?

I’ve been talking about the rainforest but I’m actually much more attracted to deserts. I can understand why so many religious figures have been drawn to the desert because you feel like your own mind expands to fill the space. There’s room for all your dreams and aspirations to grow.

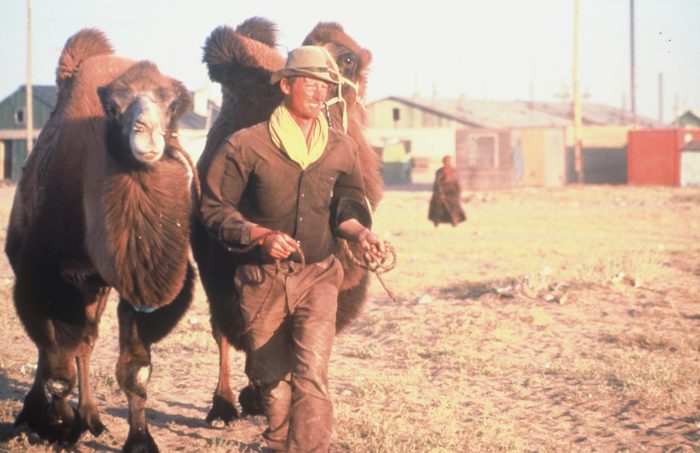

I remember sitting by myself in the Mongolian desert, looking at this extraordinary sunset and thinking, if only I could share that, and feeling the endless horizon; I could see where I’d be walking in two days’ time. I remember I sat on a rock and saw a snake beside me. In the forest it could be alarming, but there I felt a connection with the snake because it was a member of the living community.

Is there a souvenir you’ve brought back from your travels that has particular significance to you?

I’ve got so many bows and arrows, but I actually just came across an old stone axe from New Guinea. It’s amazing to think that the person who gave it to be used this stone implement as their tool. It’s a piece of human history.

Where are you most intrigued to go next?

There’s the Taklamakan desert on the Silk Road in China. The name means, if you go in you won’t come back. And there’s the Tepui area in Venezuela and Guyana, which has a lot of sinkholes that people haven’t yet been down. It’s the area where Angel Falls is – the highest waterfall in the world – and is a place of spectacular proportions, with so many secrets. I started in that area on my first expedition, so it still haunts me and I have a special connection with it.

I have a special connection with Papua New Guinea too. I’d love to know what happened to the Obini people, who I made contact with just across the border from Papua New Guinea [in West Papua]. I had to leave because they wanted to start a war with my guides, and that’s the last anyone has seen of them. Missionaries in the area have never even heard of the Obini, so I’d love to trace them and find out what happened to them.

Do you have any upcoming plans?

I want to go to Africa. I’ve been talking to a specialist in chimpanzees. I’m interested in them because they’re our nearest relative, and there are stories of a primate that’s half chimpanzee, half gorilla. There are more and more stories of this in the Congo, so I’d like to get to the bottom of that, find out what species there are and get to know chimpanzees.

Benedict’s latest novel, which is set in the Congo, will be published in 2015.